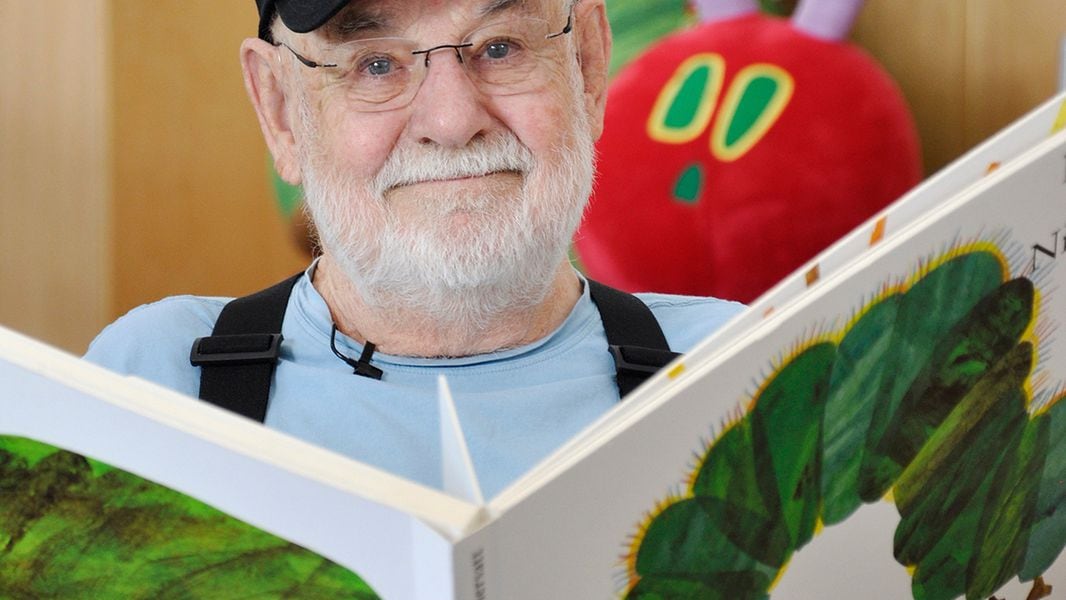

Beloved children’s book author and artist Eric Carle passed away on Wednesday (5/26/21) at the age of 91. Obituaries and celebrations of his life and achievements can be found at The New York Times, The Washington Post, and National Public Radio. To be reminded of his remarkable gifts to American visual culture, visit the website of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, MA. And Carle had deep connections to the High Country: in retirement, Eric and Barbara Carle frequently lived in their home in Blowing Rock, Carle did signings and readings at Appalachian State University and the Blowing Rock Library, and in 2019, ASU’s Reich College of Education hosted a series of events celebrating the 50th anniversary of Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. (36 images of Carle’s characters are on permanent display on the third and fourth floors of ASU’s Education Building.)

As Carle says, “We have eyes, and we’re looking at stuff all the time, all day long. And I just think that whatever our eyes touch should be beautiful, tasteful, appealing, and important.”

Last Monday (5/24) was Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday! In addition to his influence on music and literature (he won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”), Dylan has also had an impact on American visuals. Milton Glaser is widely considered one of the most important graphic designers of the past seventy years, and his psychedelic portrait of Dylan (above) is so iconic that it was the signature image for a 2008 documentary about Glaser, To Inform and Delight. And from 2006 to 2009, Dylan hosted The Theme Time Radio Hour, a satellite radio show whose poster (below) was drawn by the amazing cartoonist Jaime Hernandez. You can find all the episodes of The Theme Time Radio Hour archived here; also read Stereogum’s Dylan Birthday roundtable, where 86 other musicians discuss their favorite Dylan songs.

Ever take a picture without using a camera or cell phone? There are types of photographs—called rayograms (named after the surrealist Man Ray, who discovered the process by accident) or photograms—which are created by laying something physical (pennies, springs, even body parts) on sensitive photographic paper and then flashing light in the direction of the paper. The results are shadowy, strange, abstract, and compelling. Here is an article about how photograms work, along with a history of the procedure; here is a catalog of contemporary photogram artists, including Floris Neusüss, who “shot” the silhouetted body shown above. Also, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art gives us a short video on Man Ray and his “Crimes Against Photography!”

Ever take a picture without using a camera or cell phone? There are types of photographs—called rayograms (named after the surrealist Man Ray, who discovered the process by accident) or photograms—which are created by laying something physical (pennies, springs, even body parts) on sensitive photographic paper and then flashing light in the direction of the paper. The results are shadowy, strange, abstract, and compelling. Here is an article about how photograms work, along with a history of the procedure; here is a catalog of contemporary photogram artists, including Floris Neusüss, who “shot” the silhouetted body shown above. Also, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art gives us a short video on Man Ray and his “Crimes Against Photography!”

On May 15, we celebrated the 15th anniversary of the first appearance of Liô, Mark Tatulli’s oddball, wordless comic strip, in American newspapers. The title character is a strange, button-eyed child who communes with aliens, monsters, fellow comic strip stars, his disturbingly sentient cat, and the Grim Reaper, even while befuddling normal adults like his long-suffering father and the Principal at (where else?) Harryhausen Elementary. (This set-up makes Tatulli’s Halloween strips extra-special; check out a collection of these October surprises.) The strip is available online at GoComics, along with a short interview with Tatulli to celebrate Liô’s birthday. And I can’t resist posting one more Peanuts-themed strip below…

The Stanford University Library site refers to public domain works as “creative materials that are not protected by intellectual property laws such as copyright, trademark, or patent laws. The public owns these works, not an individual author or artist. Anyone can use a public domain work without obtaining permission.” This is stuff that you can print, post online, publish in your own zines, and play with as you like. One amazing archive belongs to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, who in 2017 declared all the 400,000+ public-domain artifacts in its collection available “to use, share, and remix—without restriction.” The Met has a page where you can learn more about their public domain holdings—with themed collections (“Arms and Armor,” “Cats,” and paintings saved from the ravages of World War II)—but you can also just dive into this enormous picture trove. One example: Federico Barocci’s Head of an Old Woman Looking to Lower Right (Saint Elizabeth), painted between 1584 and 1586.

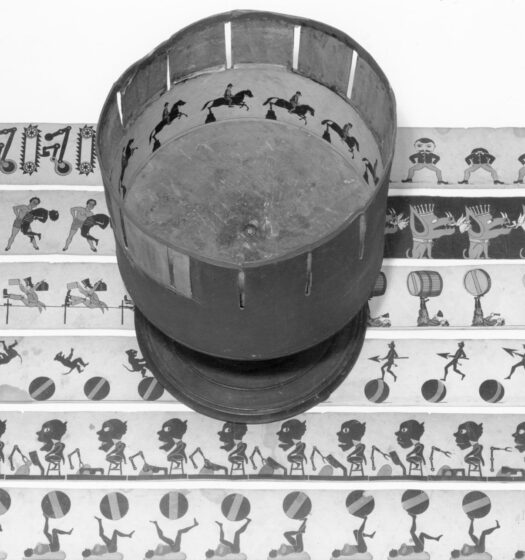

A zoetrope is a 19th century toy that creates the illusion of movement through two elements: a spinning, round drum with horizontal slits cut into it at regular intervals, and a filmstrip—images of incremental motion—attached to the inside of the drum. (The picture to the left is a zoetrope that’s over a century old.) When a zoetrope spins, and a spectator looks through the slits at the far side of the drum, the pictures seem to move. It’s easier to see than to explain: look at this. Also watch animator Eric Dyer’s 2016 TED talk about the new directions he’s taken the zoetrope, such as the “zoetrope tunnel,” a sculpture that dramatizes a cure for Dyer’s own gradual loss of vision. Another new invention is 3-D zoetrope imagery, created through combining the repetition of the filmstrip and the flicker effect of traditional zoetropes with 3-D models. Check out this 3-D zoetrope constructed by Pixar to demonstrate the principles of animation, and also see below how the genius behind the “marvelous media engine” Twitter account uses similar principles to create a moving My Neighbor Totoro jewel box.

A zoetrope is a 19th century toy that creates the illusion of movement through two elements: a spinning, round drum with horizontal slits cut into it at regular intervals, and a filmstrip—images of incremental motion—attached to the inside of the drum. (The picture to the left is a zoetrope that’s over a century old.) When a zoetrope spins, and a spectator looks through the slits at the far side of the drum, the pictures seem to move. It’s easier to see than to explain: look at this. Also watch animator Eric Dyer’s 2016 TED talk about the new directions he’s taken the zoetrope, such as the “zoetrope tunnel,” a sculpture that dramatizes a cure for Dyer’s own gradual loss of vision. Another new invention is 3-D zoetrope imagery, created through combining the repetition of the filmstrip and the flicker effect of traditional zoetropes with 3-D models. Check out this 3-D zoetrope constructed by Pixar to demonstrate the principles of animation, and also see below how the genius behind the “marvelous media engine” Twitter account uses similar principles to create a moving My Neighbor Totoro jewel box.

Finished another zoetrope. This time I wanted to make a tribute to one of the greatest animators, Hayao Miyazaki. #StudioGhibli #totoro #catbus #stopmotionanimation #vfx pic.twitter.com/viMGhFVsEZ

— marvelous media engine (@EngineMarvelous) May 19, 2021

This weekly blog post is written and compiled by Craig Fischer. To send along recommendations, ideas, and comments, contact Craig at [email protected] [.]