This is the 52nd issue of the Playhouse Comics Club, which means I’ve been assembling and posting the Club every Friday for a year. To mark the occasion, and to acknowledge Earth Day, I’ve done something different this week: a long interview with Jennie Carlisle, the curator of my favorite art installation of the pandemic—located here in Boone, North Carolina, no less. I hope that Playhouse parents bring their families to the campus of Appalachian State University to explore “Signs, Wonders, Blunders” before the exhibit leaves campus at the end of the spring 2021 semester. –Craig Fischer

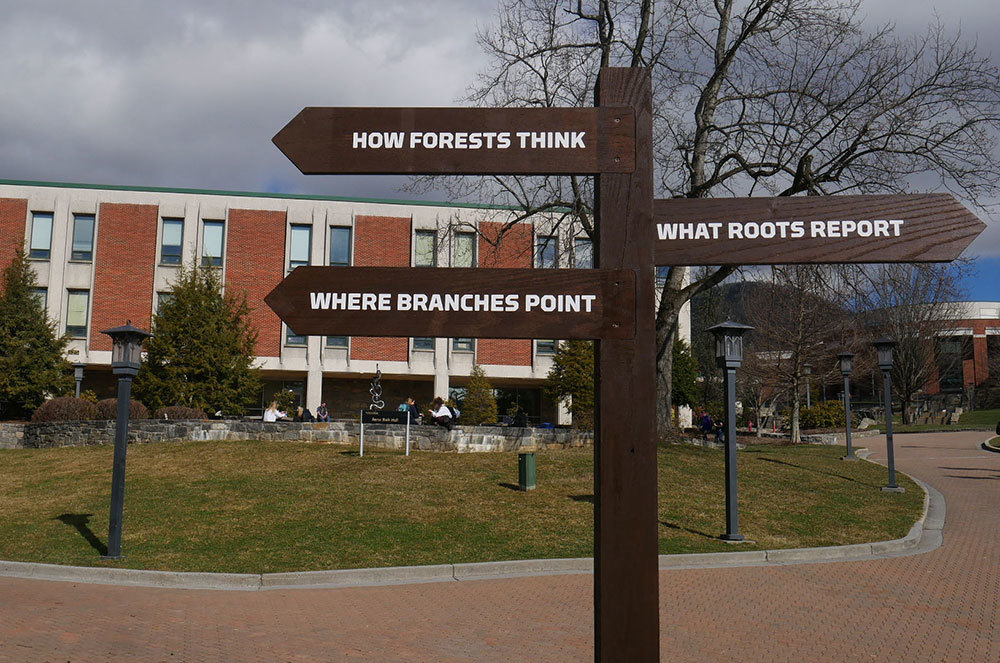

On February 12, 2020, I walked out the back door of Edwin Duncan Hall, the Appalachian State University building where I work, and I saw something new on campus: a wooden trail marker set in the ground, with three horizontal signs attached near the top of the post. The words on the signs were unusual, so I took a photo of the entire marker.

I posted this picture on Facebook with a glib remark—“They put these signs up outside of my building and thank God they did, I thought I might get lost”—but I also Googled the terms I didn’t know, “Hyperobjects” and “Vibrant Matter.” Both are recent concepts that describe humankind’s relationship(s) to the natural world. Timothy Morton defines hyperobjects as those presences and conditions “that you can study and think about and compute, but that are not so easy to see directly” because of their sheer size, such as the environmental symptoms of global warming. And vibrant matter: in her book of the same name, philosopher Jane Bennett argues that everything is alive, interdependent, and in flux—including rocks, garbage piles, and the parasites that symbiotically feed on our bodies. Everything is vibrant matter charged with life, a worldview that challenges any notion of humanity as outside or above nature and its processes. This trail marker was telling me stranger things about the world than I’d heard in a long time.

Over the next couple of weeks, I noticed similar markers standing around campus, though these featured different terms and phrases, some unfamiliar to me: Dendrometers, Larsen-B, Laudato Si! (For a list of all the markers and their locations, go here.) And by the end of February, new signs stapled to the posts appeared with the following text:

What do I NEED

to KNOW

for the planet

to thrive?

SIGNS, WONDERS, BLUNDERS

is a campus wide

art installation by

DEAR CLIMATE

Supported by

Appalachian’s

Climate Stories

COLLABORATIVE

At first, I enjoyed stumbling across previously-unseen “Signs, Wonders, Blunders” trail markers while walking across campus; the design of the project invited me to look for connections among the three terms displayed by each trail marker, and, more broadly, the links among all thirteen markers. But what started as an intellectual exercise became emotional for me when the Covid-19 pandemic struck, and signs like “Sixth Extinction” and “Slow Violence” presided over an abandoned university.

Meanwhile, a Facebook friend responded to my trail marker photo by telling me that the prime mover behind this project was Jennie Carlisle. An instructor in ASU’s Department of Art (she teaches classes in art management, exhibition practice, and other topics), Carlisle is also the curator for the Catherine Smith Gallery in Appalachian’s Schaefer Center for the Performing Arts. I interviewed Carlisle about the “Signs, Wonders, Blunders” installation, and learned about the New York-based ecological art collective Dear Climate, about the spiritual heart of the project, and about the importance of processing the pain of isolation we all feel because of the pandemic and quarantine.

Meanwhile, a Facebook friend responded to my trail marker photo by telling me that the prime mover behind this project was Jennie Carlisle. An instructor in ASU’s Department of Art (she teaches classes in art management, exhibition practice, and other topics), Carlisle is also the curator for the Catherine Smith Gallery in Appalachian’s Schaefer Center for the Performing Arts. I interviewed Carlisle about the “Signs, Wonders, Blunders” installation, and learned about the New York-based ecological art collective Dear Climate, about the spiritual heart of the project, and about the importance of processing the pain of isolation we all feel because of the pandemic and quarantine.

Our chat follows. My thanks to Jennie for her time and thoughtfulness.

Craig Fischer: When were the Signs, Wonders, Blunders trail markers installed on campus? I took a picture of the first one I saw, the one behind Edwin Duncan Hall near the Rankin rock garden, on February 12. Did the project go up in early February 2020?

Jennie Carlisle: It did. The project was conceived a year prior. I had received a grant through ASU’s Office of the Chancellor to commission a project with the Dear Climate collective. Then we went into a period of rigorous discussion about what we wanted to create and how it would combine with the dynamics of Climate Stories, a learning community on campus. We thought about the ways this project could be used for a whole host of educational programs. It really took about a year to produce, and honestly, I did it too fast. We got to the place where I could physically install the trail markers in February, but because that was such a major push, I wasn’t able to organize all the educational scaffolding I wanted around the project.

But you brought artists from Dear Climate to campus.

There are three artists that are part of that collective, and two [Una Chaudhuri and Marina Zurkow] came to ASU in fall 2019. We had one visit scheduled for spring 2020 [from Oliver Kellhammer], but we had to cancel his appearance because of the pandemic.

Would you tell us a little about Dear Climate? Who are the Dear Climate members, and what do they try to achieve with their art?

Dear Climate is an artists’ collective based in New York City that’s made up of three core members. Marina Zurkow works across many different media: she does animation, participatory work, collage-making, and technology-based art projects. There’s Una Chaudhuri, an English professor and someone deeply involved with environmental humanities for the past thirty years. She has a strong connection to the world of theater, not only as a critic and writer, but also as someone passionate about live production. The last member of the group is Oliver Kellhammer, an artist who works through living systems—making art with living forms, forests, etc. They come together as Dear Climate to think about ways we can recalibrate our relationship to the more-than-human world, how we can change our habits towards climate.

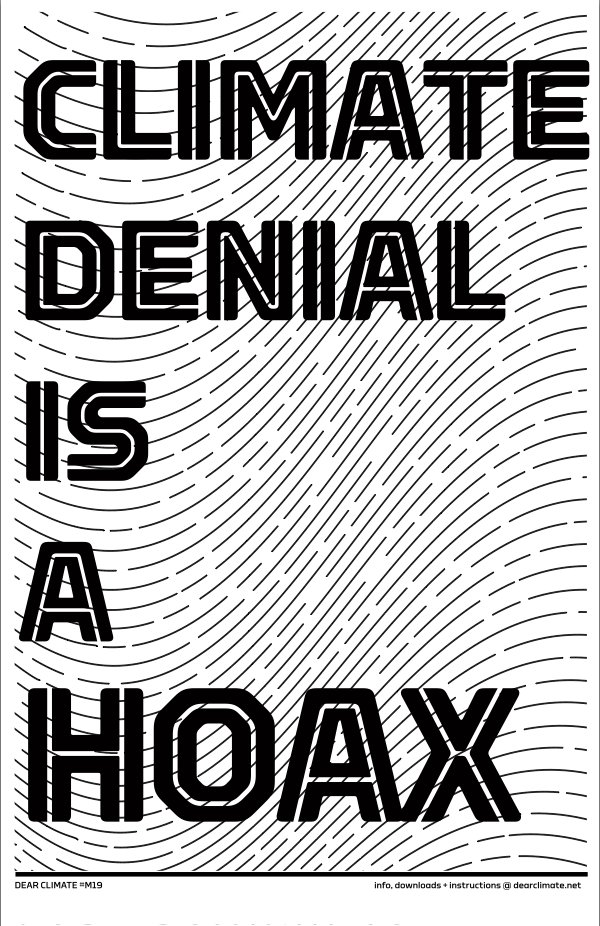

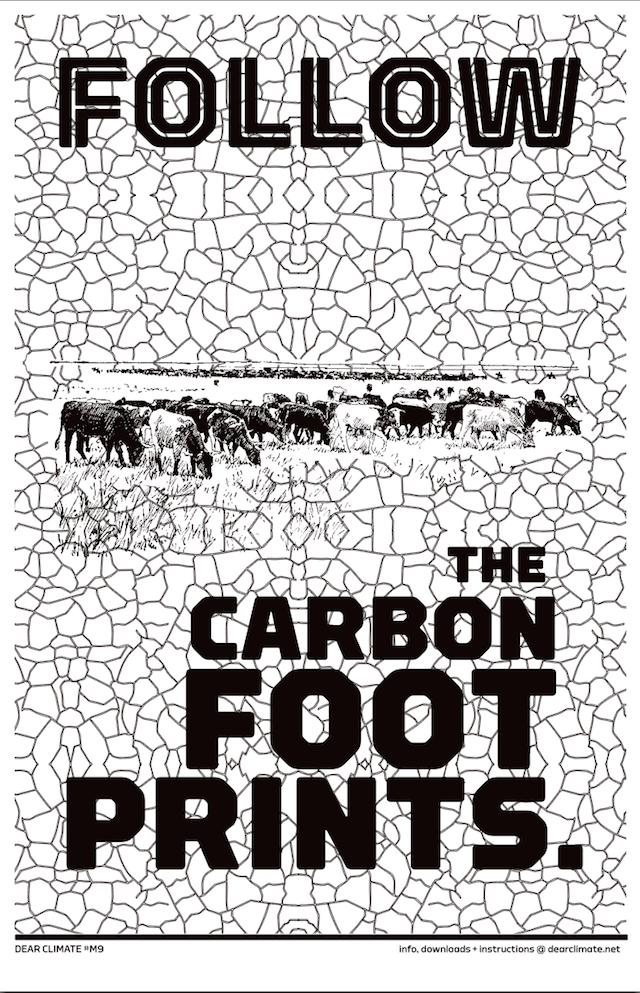

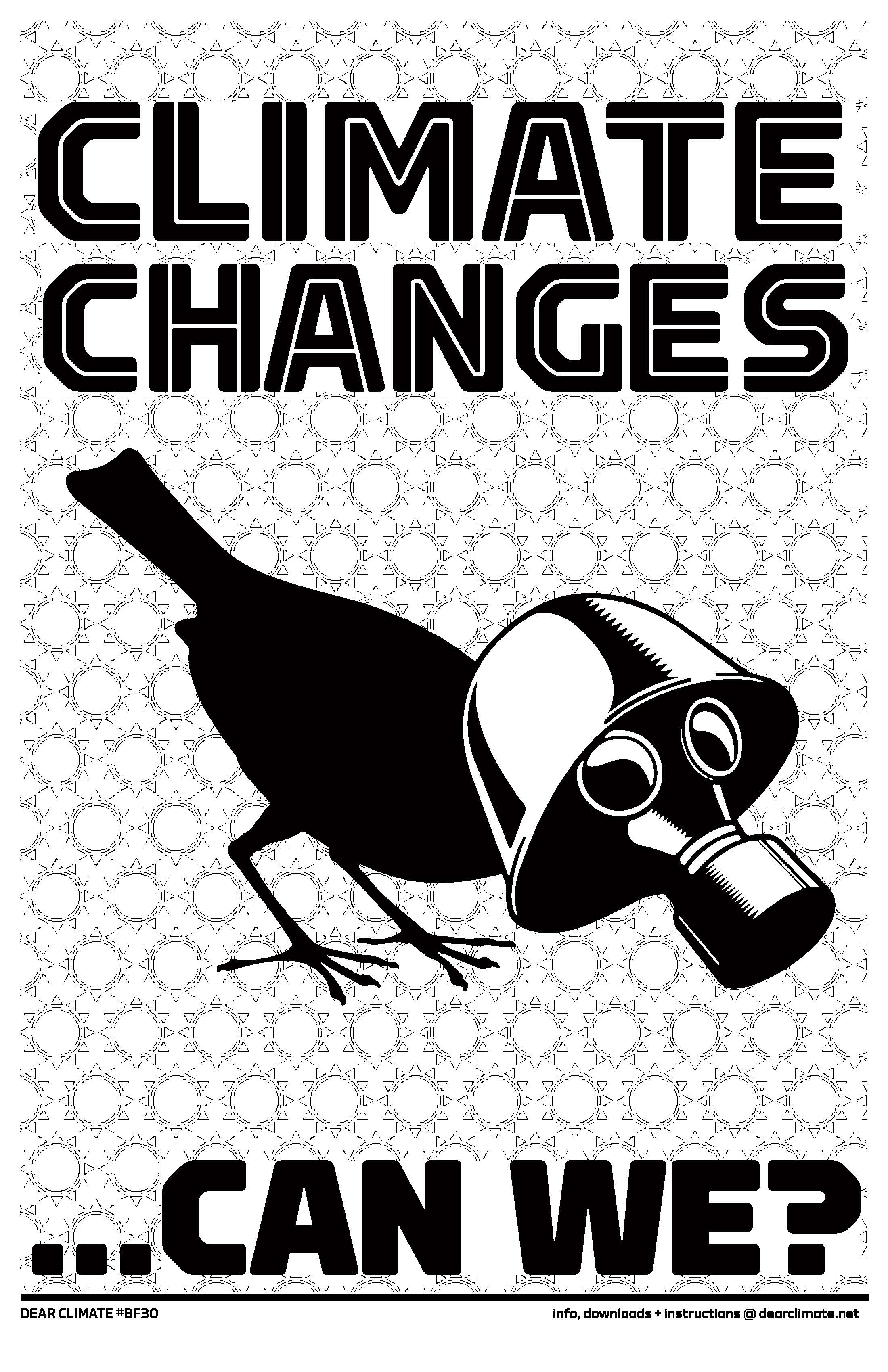

Their projects have taken a lot of different forms. They create posters meant to be a fast and quippy way to engage with these issues. Those posters can be used by anybody—you can go to their website now, download them, post them anywhere…

Those are the posters that say, “Let Them Breathe CO2” and other environmental slogans, right?

Those are the posters that say, “Let Them Breathe CO2” and other environmental slogans, right?

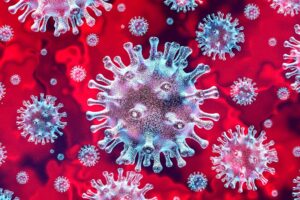

Exactly. They’re powerful! Dear Climate also does incredible audio meditations, hyper-narrative guides that walk you through a set of different scenarios. They alter your mental space. I’m obsessed with one called “Hello Virus,” which asks you to be aware that you’re breathing in viruses, and what that exchange looks like. Pretty amazing. They’ve also done other sign-driven installations, including one that represents a United Nations of both human and non-human entities—“animals, plants, geophysical forces.”

Signs, Wonders, Blunders relies a lot on language to recalibrate our relationship to nature.

That’s something that attracted me to this project, because there is a sense of imagery through the language Dear Climate selected—we create images in our minds as we read their words. That’s very interesting for cross-disciplinary exchanges, this combination of words with images.

When I look at the trail markers and see certain phrases, I do get certain images in my mind. You can’t read the phrase “Larsen-B” and not picture glaciers crashing down. [Pause] Talking about this topic is depressing.

The project doesn’t sugarcoat any of the damage of climate change. It’s about putting these topics out in the open, so we have to process them. Having signs that say “Larsen-B” and “Great Barrier Reef” and connecting the destruction of the two is hard. Hopefully the project is eliciting deep feelings for other people encountering it too.

Emphasized over and over are all the obstacles we’re going to have to face in order to return to a healthy relationship with our ecosystem. The slow violence that will happen for millennia until we straighten things out…

Dear Climate as a group is deeply concerned with climate chaos and thinking about where we went wrong as a civilization. But what’s novel about this project and their approach is their message that climate change is a symptom of our disordered relationship with the more-than-human world.

You’re involved with the Climate Stories community on campus—was it you and the Collective that reached out to Dear Climate? Do you have personal connections with the artists?

I’ve been interested in art and social change for a long time, and in graduate school I studied how art and art communities interact with social movements, especially in post-colonial Africa, where art was involved in the move from a colonial mentality to establishing the identities of newly formed states. I’m fascinated with movement-building and how art contributes to large-scale changes in how we understand ourselves personally and socially.

I’ve also been loosely involved with different environmental movements over the past twenty-five years. In the last decade, I became quietly interested in what I call “flares,” hot moments where climate was registered as a major issue in both cultural conversations and in the arts. I wanted to be more directly involved in those flares.

Early in my career, I studied art from a more intellectual, art-historical perspective, but now I want to be alongside artists, working with them. I want to be someone who blends scholarly thinking and research with art-making.

My model for this mixed approach is Una Chaudhuri. I met Chaudhuri at a week-long workshop in New York City, and I was incredibly impressed by her. She blew me away. Listening to how she thinks and speaks was profound. I knew this was somebody I wanted to work with—I immediately wanted to bring her to campus. This was before I knew about Dear Climate, but after I found out about the collective, I was attracted to the fact that they’re a group of artists from different perspectives and backgrounds, making unique disciplinary connections. So I invited them to collaborate with me on writing a grant and developing a project.

Were you surprised that the university greenlighted Signs, Wonders, Blunders?

I’ve been so impressed that they went ahead with the project. There’s a lot of public art on the ASU campus, but it tends to be discrete—separate pieces—and without language. It’s also not politically explicit; most of the public art uses abstract forms to express abstract ideas, so viewers make the decision to engage with it. But Signs, Wonders, Blunders is different. The trail markers are connected, they range across campus, they don’t live on pedestals, and they’re direct and political in their messaging.

The basic message of the project is: “We have the change from the ground up.”

The basic message of the project is: “We have the change from the ground up.”

I love how direct the title is: Signs, Wonders, Blunders. There’s even a religious ideology at play in the project. The exhibit references how Christians are having conversations about the environment. One of the trail markers includes the words Laudato Si! (Praise Be to You!, 2015), which is the title of Pope Francis’ encyclical about our responsibility to care for our “common home,” the natural world. Words like “signs” and “wonders” evoke Christianity, since evangelicals argue that miraculous conditions prove the existence of God. It’s a bold move to exhibit a project as political, as ideological, and as religious as Signs, Wonders, Blunders at a politically-neutral public university like ASU.

But some evangelicals approach issues of the environment differently. In Boone, I’ve seen bumper stickers that say, “The Earth is Not my Home,” expressing the evangelical belief that this world is transitory, and that each person’s individual spiritual quest for God’s grace is more important than preserving the natural world.

I had a student who wrote about the religious themes in Signs, looking at how Christian apocalypse narratives about natural catastrophe are being politicized to achieve some environmentally-progressive aims. But it’s true that some evangelicals argue that if the collapse of the environment is a sign of the End Times, then who are we to stand in the way? [laughter] Do we really want that kind of mass suffering?

The Rapture sounds like a great idea, but the Tribulations afterward sound terrible. [Laughter] Before, you mentioned that the project was blunt and political in its message, but my first response was, “What the Hell is this?” The first trail marker I saw was the one behind Edwin Duncan, which says “Hyperobjects,” “Vibrant Matter” and “Stranger Things.” Early on, you hadn’t put explanatory notes on the markers yet, so I was completely confused. Were you hoping to generate that confusion when you were planning the project with Dear Climate?

Yeah, absolutely. The language on the markers is weird: there’s a tension, a rub, between critical language like “Vibrant Matter”—though some other words strike a different tone—and the slippery meanings created by the collections of words on each marker. It’s not meant to add up into a neat package. It’s not a bunch of activist slogans. You can’t nail down the meanings of all the language. You grapple with the strangeness of the sign and its location. Probably the point of reference for most students would be the TV show Stranger Things; they wonder, “Why the heck is Stranger Things on this sign?” That title suddenly connects to the strangeness of living in this period of climate change…

I like how the language on the markers can shift from scholarly language like “Hyperobjects” to a pop culture reference like Stranger Things.

The project is very much about that kind of code-switching: it places all this language generated in culture into a new context.

Let me return to the point that you made about the explanatory plaques on the markers. Originally, there were not going to be any plaques.

I had a feeling that was the case, and I liked the strangeness of being given these trail markers without any guide, without explanatory text telling us what they are.

I think the project is still odd enough to have that effect, even though the plaques do define the markers as art objects. Without the plaques, you had no idea what was going on: “Is this intentional? Is this authorized?” You just can’t tell! [Laughs]

I’ll tell you the story of the plaques. Part of it was intentional, and part of it was not. When we conceived the project, there weren’t going to be any explanations, but the university said, “You have to tell them that it’s art.” I get it from ASU’s perspective: it makes the project more educational and accessible. The plaques help viewers go back to the trail markers and understand how to contextualize them. I was OK with that, but not necessarily in love with the quarantining of these signs—suddenly you can designate them as “art,” which makes the disruption of the project less effective.

But there was a brief period where the markers were up without the explanatory plaques…

That was not intentional, but I love that it happened. Honestly, it was a time issue. We installed the trail markers, and then as quickly as I could, I went around and put up the plaques, but there were two weeks where the project just sat there on campus, without any clarification.

I’m so glad the project had that moment. It got to be fully disruptive during those two weeks, and then when I put up the plaques, people got even more interested in Signs, Wonders, Blunders. And folks also calmed down: “Don’t worry, it’s a harmless art project…!” [Laughter]

Both “Hyperobjects” and “Vibrant Matter” are terms that push us outside a human-centered way of looking at the environment, into a perspective so much bigger than we are.

Both “Hyperobjects” and “Vibrant Matter” are terms that push us outside a human-centered way of looking at the environment, into a perspective so much bigger than we are.

That’s the dominant idea of the project: How do we understand these bigger systems and trends? How can we understand the agency of the geophysical world? Humans are reshaping the world, even as we don’t understand how that world works—we’re too stuck in our own heads, in our own idea of culture. We have small ideas about who is part of our society. Maybe we include pets and other companion species, but it’s still a limited notion of who gets included in our community.

We even define racist divisions inside of our own species. [Pause.] I need to bring up something upsetting: the trail marker behind Edwin Duncan looks like it’s been vandalized.

There are two signs that have been damaged. My assumption is that they’ve been vandalized, but I’m not entirely sure. I go around the campus to maintain the markers. I wear all the hats. I do it all. [Laughs] There’s being a curator, and I do maintenance too! While making the rounds with my bucket [Laughs] I saw the two signs—“Vibrant Matter” and “Stranger Things”—missing from the marker. And I thought it was vandalism at first, or at least someone playing too hard on the sign. But then I saw a marker battered by the wind, and the way that sign was jockeying in its place made me wonder if the wind damaged the other markers too. And with the Duncan / Rankin marker, I took down “Stranger Things” so I could use it as a guide in getting the other plates remade.

Originally, “Vibrant Matter” was gone, and another marker, “Buen Vivir”— random choices for vandalism. I would be very surprised if there were vandals with direct connections to those phrases, who reacted enough to the language to tear those signs down. It was just somebody deciding, “Oh, wouldn’t it be fun to jump up on this wooden sign and swing around?” And then the sign snaps off. Or somebody thinks it’s a silly project, and lacks respect for it, and they break it. The damage isn’t a deep reaction to the project.

That restores my faith in humanity. I thought some drunk students tore off the signs to hang up in their dorm rooms or apartments. I hope it was accidental.

It could be what you describe, but then it’s still a pretty ignorant move: “I don’t like this thing,” instead of someone trying to figure out what the project is doing. [Laughs] [Update: Jennie has repaired all the signs and markers.]

What kind of role do you think walking has in our perception of the exhibit? Is it important that the project consists of markers about the environment that are embedded in the environment? Do you think moving from one marker to another shapes what the project says to us?

One of the things I like about this project is how it’s so open-ended. If you go to the website and see the map, you’ll see I’ve ordered the markers from “A” to “M”: thirteen stops. But you’re meant to encounter the markers freely. You make your own routes and connections in an open, networked way, as you experience them every day (if you work on campus). The project unrolls in an exploratory manner: it speaks to the relationships among wonder, wondering and wandering. We’re curiosity-driven, we’re moved by the next spark of insight we feel from the trail markers, and we experience moments where ideas and thoughts coalesce, temporarily.

And then we start to see patterns.

And the patterns that are created are highly individualized. There is an overriding logic to how the language on the trail markets was selected: to create a syllabus of ideas, an expanded interdisciplinary canon for environmental humanities. But if you’re encountering the markers by accident, inside the installation, you go from one trio of statements to the next, and you’re asked to do a lot of work to unpack connections.

But that’s the fun of it! Signs, Wonders, Blunders is about serious issues, but I find the pattern-making and strangeness you describe delightful.

I’m glad that you felt that. I don’t use the word “work” as a pejorative term. The project’s playful, right? [Laughter] It’s like a puzzle you turn around in your mind. When you discover something new, you think, “How does that fit into this framework?”

And through it all, there’s that one question that overrides everything: what do I need to know for the planet to thrive? No matter where you are in the project, you’re still guided back to that question as an entry point for understanding the flow among trail markers.

What kinds of additional resonances did Signs, Wonders, Blunders take on when the pandemic hit? For me, the project went from being an interesting formal exploration of environmental issues to a prophecy of life out of balance.

What kinds of additional resonances did Signs, Wonders, Blunders take on when the pandemic hit? For me, the project went from being an interesting formal exploration of environmental issues to a prophecy of life out of balance.

I felt haunted by how the installation speaks to our derangement with the more-than-human world. Climate change is real, and it’s unfolding in all these diverse ways, but it still feels abstract, like it’s not impacting us directly. There’s always this sense of deferral with climate change. We can see its physical symptoms, we know the political, economic and social problems connected with it, but it still feels like an abstract apocalypse to us.

But Coronavirus’ apocalypse is tangible. It’s put us in a place of immediate pain. We’re all experiencing the pandemic differently, but there’s a widespread feeling that the Covid-19 crisis is a clear sign of our alienation from the larger natural order. The virus challenges our assumptions about human exceptionalism; it’s a direct result of our exploitation of the earth’s minerals and our decimation of the forests. We’ve created harsh living conditions for other species, and now when they get sick, we get sick. We are a vulnerable species, just like all the others, and we are making this planet unlivable for us too.

I feel helpless. Every time I feel like I should do something for the environment, I think, “I can recycle” or “I can drive a hybrid car”—but changing larger economic and political systems to foster greater harmony between humans and the natural world seems impossible. And then Coronavirus comes along and makes that idea of helplessness real and immediate.

Yes, but we’re now questioning the ideas that our political ideas are intractable, that we can’t stop our economy, that we always have to accelerate and grow, grow, grow. We’re questioning consumerism and the structure of our global economy. I live in an apartment above a garage in a rural town in the middle of the woods, and here’s my birds’ eye view: everything happening now suggests that our individual actions do matter, that we can change our minds and habits, and we can do it fast. Now what does it take to build on the adaptability, resiliency and social connections that came about because of the pandemic? Our economy has ground to a halt, our ways of being in community has radically shifted, and we’ve made big changes. What would our world look like if we decided, intentionally, to make more changes?

We’re already seeing signs of nature springing back, as a result of less driving, less consumption, less capitalism: dolphins return to the canals of Venice, etc.

Exactly. When we think about the meat industry, about the Covid-19 outbreak at the Tyson chicken processing plant in Wilkesboro, we realize the health implications of slaughterhouses and the ethical effects of meat. And maybe more people will start eating in a more socially responsible manner.

You’re renewing my faith in humanity on several levels today. [Laughter] Thank you, Jennie!

Sure! I try not to give in to despair. I’m always looking for the way forward, the new opportunity.

The great thing about the project is that in encompasses feelings of pessimism even while mapping out concepts for going forward and repairing our relationship with the environment.

As I was thinking about which trail markers to talk about in this interview, the “Great Derangements / Catastrophes / Small Screw-Ups” one came to mind, partially because we’re living through a “Great Derangement” now. Everyone’s struggling to figure out how to process the events of 2020. “Catastrophes” and “Small Screw-Ups”: I can’t help but think of Coronavirus. What are the small screw-ups we’re doing to undermine the health and safety of other people every day? Or what about the failures of our political leaders to lead us through the pandemic? Now that’s a catastrophe.

It’s the study that came out from Cornell University in May 2020, which indicated that if we had started social distancing two week earlier, thousands of lives would’ve been saved.

That makes me so angry.

On the other hand, the trail marker that felt most inspiring to me, that haunted me in the best way, is the one in Durham Park, the one that says: “Stay with the trouble / Burst your bubble / Study the rubble.” That’s a useful mantra for me. It’s hard right now to live with the pain, the discomfort, and the frustration of climate change. It’s hard work to do that. Asking us to change in such a complete way takes work.

On the individual level, it means questioning our own pleasures. How much of my life is invested in hyper-capitalism? Is that sustainable? I love to travel—but I shouldn’t be getting on that plane, because I’m poisoning the environment every time I fly.

Right now, we would really prefer to be with other people, but it’s unhealthy. We need to stay with how that feels. All we can do is be in this lonely space, with these emotions.

The Coronavirus doesn’t see class; it doesn’t see privilege. Some populations are hit harder by the pandemic, absolutely, but this is a moment where everyone feels like they’re reduced to an animal body. Right now, you can be wealthy and still be very lonely. And there’s potential for empathy in this moment that can transcend class and buffers of privilege.

This weekly blog post is written and compiled by Craig Fischer. To send along recommendations, ideas, and comments, contact Craig at [email protected] [.]